Clyde Stubblefield

an in-depth interview with the future Hall of Famer!

by Teri Barr

September 2015

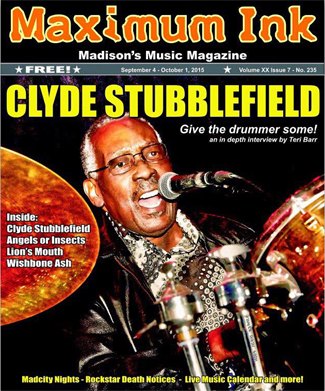

Clyde Stubblefield on stage at the High Noon Saloon 8/30/2015

photo by Mary Sweeney Photography

“I am a happy man.”

Talking with Clyde Stubblefield during the past couple of weeks, the one feeling he’s pointed out each time, is his happiness. “I am getting so much love, and being back on stage playing my drums is making me a happy, happy man,” the 72 year old says with a smile.

To understand this current focus on Stubblefield, the fundraising shows to establish a music scholarship and a push to get him nominated for induction in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, you have to dig back into his past. Born in Tennessee, he started playing drums after seeing musicians in a parade. But from the start, he created his own rhythm, without any formal training. ”I’d listen to the things happening around me. The train, traffic, work at the factory. And I’d then make up some beats to go along with it,” Stubblefield says. The unique style made him stand out when James Brown heard him play at a bar in Georgia. It was an unanticipated beginning in the music business, for a man who would go on to forever be known, as the funky drummer. “Just always put down whatever groove I wanted. No one ever told me what to do, and things just always sort of happened,” Stubblefield says. Brown asked him to play shows – first in New York at the Apollo Theater, then it was on to Europe. For more than 6 years, he kept that one-of-a-kind, funky, R & B beat going for Brown. Yet ask him about that time now, and Stubblefield seems surprised. “All of it. It all just sort of happened. I don’t plan anything, so everything we did was a surprise. Traveling to different states and countries to play music? I sure didn’t plan it,” Stubblefield says.

He also didn’t plan, and couldn’t know, his unique drumming style would be what helped drive the creation of some huge hits for James Brown. Songs like “Cold Sweat,” “There was a Time,” “I Got the Feelin,’” “Say it Loud – I’m Black and I’m Proud;” topped the charts. He tells me luckily, the process in the studio, was pretty loose. “Usually the band would just start with some grooves, and I would play some drum riffs, nothing in particular,” Stubblefield says, “And the bass, guitar, horns; we’d come up with a song and just keep it up until Brown came in and would add his words to it.” The 1970’s “Funky Drummer” song included a Stubblefield solo, and those 20-seconds have became some of the most sampled rhythm patterns of all time. Public Enemy’s “Bring the Noise,” LL Cool J’s “Momma Said Knock You Out,” are just two examples, but Stubblefield himself is sure it’s been used over and over, hundreds of times by all types of artists. Unfortunately, he’s received little credit or cash for the sample. And if there is any sort of royalty payment made, it goes to Brown, who is noted as the writer of the song. Talking with him about it, Stubblefield says, “This is about the only thing that makes me unhappy. He’d call your name out on a song or something like that, but he basically cared about himself.” Brown was notorious for not giving his stellar musicians credit on albums or at shows, though as Stubblefield mentioned, would yell out on a regular basis to “give the drummer some.” It meant it was time for a solo, and for the audience to recognize the man behind the drum set. Only in the last several years has Stubblefield even sought to get the copyright for any of his rhythms, and claims it’s not so much the money he’d like anymore, it’s more about the recognition. “My drum patterns are used on so many songs. No credit feels almost worse than no cash for it at this point,” Stubblefield says. He’s also brutally honest about a movie made a few years ago, and based on the lives of Brown and the band. “I didn’t like it,” Stubblefield says, “It didn’t really have action, at least the way I remember it.” Again, little regard for the role Stubblefield played in helping create the legend that is James Brown.

Efforts here to create Stubblefield’s own legendary status – by acknowledging his immense talent, while being sure his name lives on – are now feverishly underway. There’s also a bit of hurry-up felt in the undertone of all the excitement for Stubblefield. He isn’t well, telling me during a phone conversation, the dialysis he needs three to four times a week, just beats him up. This particular afternoon, he talked with me while laying in bed, with no plans to get up until the following day. He had a tumor removed several years ago, and is in the end-stage of renal disease. Preparing and rehearsing for the fundraising and recognition concerts has taken every extra bit of energy he can muster, and after the first one on August 30th, Stubblefield needed 24-hours to recuperate. But he’s not complaining. The show at High Noon Saloon was simply electric, a who’s who of musicians not only circulated in support, but took turns on stage to jam or sing with the man who’d influenced many of them. “It felt so good. I loved every minute on stage, and was able to show I haven’t really lost it. It just meant a lot to me. I’m a happy man,” he says. He’d also worried his drumming might be hampered following an accident in the kitchen of his home a year ago. “I burned my right hand while cooking, “ Stubblefield says, “And didn’t even realize it was that bad, until my wife said I better go to the doctor.” He ended up losing his thumb and part of a finger, and after recovering, had to have drumsticks retro-fitted with a special grip. He’s only played a few shows since, but doesn’t seem he’s lost a beat. It may also make the upcoming Madison dates in September and October, even more special.

Stubblefield calls a show at the (Alliant Energy Center) Coliseum a few years before he quit playing with Brown in 1971, the one that made him decide Madison might be a good place to live. He’s considered this area his home ever since. He also decided not to put down his drumsticks, and for years played a weekly show downtown with his own band (yes, he can sing, too), eventually moving to The Frequency where his nephew Brett joined him on drums. And when he decided to give up the gig due to growing health issues, Brett took it over, keeping the Stubblefield name a part of the music scene. He’d also added drumming duties for Michael Feldman’s “Whad ‘Ya Know?” radio show in 1985, and it was during this period – one of his busiest times – Stubblefield was dubbed, “the hardest working man in Madison.” He was still a full-time musician—playing, recording, touring or teaching – sharing his skills in every way possible. He wasn’t under Brown’s thumb. And he loved it. “I was being recognized here for my influence, my efforts. It was when I first realized music really does make me happy,” Stubblefield says.

So call it reciprocation. Or the reward Stubblefield is receiving for loving Madison, and allowing Madison to love him back. A few volunteers got together, and have grown into a full-blown Coalition for Recognition of Clyde Stubblefield. In just a couple of months time, the group set up a fund for a music-focused scholarship that will be awarded in Stubblefield’s name. It will keep his legacy alive for years to come. But the coalition decided it wanted more for Stubblefield, and organized three shows starring the funky drummer, including many of his musical friends. Money raised goes to the scholarship fund, while all the recognition goes to Stubblefield. “Again, it’s all so surprising,” he says, “I don’t plan anything, but I guess I’m lucky others do.” At one point during the August show, 14 musicians joined Stubblefield on stage. Expect something similar on September 11th at The Barrymore, with the final show October 8th at the Overture Center as part of the MadCity Sessions. This one will bring out Madison officials who are planning to declare it “Clyde Stubblefield Day,” and he’ll be presented with a key to the city. The past several years have finally brought him some of the credit he craved long ago. But the big one – a nomination and induction to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame—something James Brown earned in 1986, still alludes him. “My drumsticks are there,” he says, laughing. The coalition added one more item to its list of goals for Stubblefield. If his adopted home-town is recognizing his accomplishments, something his birth-town of Chattanooga did in 2014, why not the Hall of Fame? “Why not?” Stubblefield says, “Why not? I’m happy now. I’m a happy man. But that would make me even happier.”

(4225) Page Views Clyde Stubblefield Online:• Facebook • Wiki